| Iris Haeussler (2009) |

Ellen's Gift

| ||

|

|

The Bequest of Ellen Stanley

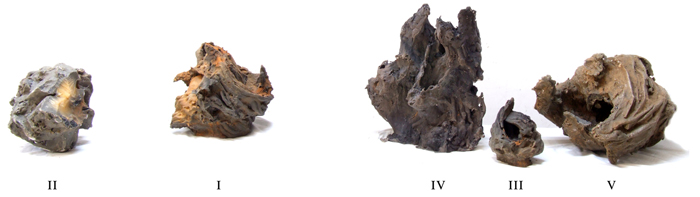

Ellen Stanley, 1895-1931 Ellen was described as a sensitive and frail child. Unusual for the time, in 1913 she was sent to university where she studied Botany. Later, she found employment as an assistant librarian. In 1919, Ellen married Arthur Stanley (1898-1957), a pharmacist. Arthur had just inherited his father's pharmacy, after his father had succumbed to the Spanish Flu. Their only child, Anne, was born in 1923 (Anne Kelley, † 2007). Shortly after giving birth, Ellen experienced a severe conversion disorder, at that time diagnosed as "hysterical blindness." Whether she indeed had no physical impairment, as her doctors claimed, or whether she had suffered a stroke, as a complication of protracted labour, cannot be determined today. Two decisive circumstances arose from the situation: she became completely blind, and she was stigmatized as a mental patient with a clinically manifest neurotic disorder. Doctors recommended that Ellen be admitted to a hospital for the insane, as they believed the newborn child exacerbated her condition. Arthur complied with the admission and took a distant cousin—Elizabeth—into the house to care for the child and the household. Elizabeth was 17 at the time. Arthur visited Ellen frequently, over time getting increasingly distressed with the situation and the environment in which Ellen was kept. Arthur arranged for her discharge into his care in the summer of 1925. Ellen's mother visited and helped settled her daughter in during this challenging time. On that occasion she brought Ellen a curious object: a cone, about the size of a sugarloaf. Apparently, as a child, Ellen's mother had once observed an old woman, who lived in a nearby shack, pouring a hot liquid into a hole in the soil; she had remembered and recovered it after the woman—whom she only knew as "Old Mary"—had died. It smelled like beeswax. Ellen's mother was convinced that Mary had practiced some form of folk medicine and hoped that the object would help Ellen somehow. This object indeed inspired the set-up for a new activity that would occupy Ellen for years to come. The child Anne recollected her mother spending her days in her room behind drawn curtains. There was a tub in the room, filled with soft clay. Anne sometimes silently observed Ellen, wearing an apron, digging holes in the clay with her hands, pausing often, reaching deeper as if searching for something, thereby creating deep cavities. Usually once a week, it was then Elizabeth's task to melt a huge pot of beeswax in the kitchen. The wax was strained through a piece of cloth into tin pots and carried to Ellen's room. Elizabeth poured it into whatever cavity Ellen had created, while Ellen and sometimes Anne would just listen to the pouring, taking in the warmth and sweet smell that suffused the whole house. The following days, Ellen would dig the solidified item out of its matrix, scrubbing it in a water filled bucket to remove residues of soft clay from the surface. Then she would playfully run her fingers along the ridges and slopes, for hours alone in her room. To maintain the necessary supply of beeswax for Ellen's compulsive "work," the family simply reclaimed the same wax by removing the sculptures from Ellen's room into the kitchen and breaking them up over and over again. While Ellen settled into a life that revolved around her activity, Arthur and Elizabeth began living the life of a couple, raising Anne, and sharing bed and table. In 1929, their child James was born. In January 1931, Ellen died of pneumonia.

Shown in: More Real? Art in the Age of Truthiness

|

Ellen Stanley's hands

|

||